Being an esports researcher in Germany is always an ambivalent experience. On the one hand, Germany was the birthplace of ESL and Freaks 4U, is the home of the League of Legends European Championship (LEC), and it can sometimes show its innovative side as seen with FC Schalke 04, as one of the first Football teams with a dedicated League of Legends team.

On the other hand, there is this emotional discussion about esports being a sport or not being a sport. Just recently, the German Olympic Sports Confederation (DOSB, shorthand for Deutscher Olympischer Sportbund) presented a legal opinion on esports, claiming that it is no sport based on the currently applicable law and, consequently, cannot be categorized as non-profit. Still, laws can be changed, and they should be changed if society is evolving. Especially in times of the digitization, we observe a massive transformation, and there is a need to deal with this change. We are experiencing the fourth industrial revolution. Moreover, that is the aspect that this struggle in dealing with esports is emblematic for the struggle of society transforming into a digitized society. Existing rules, regulations, and laws do not necessarily fit any longer in times of digitization.

Consequently, we have to rethink the categories in which we are thinking; therefore, putting esports into traditional sports categories may no longer be fitting. It may be reasonable to understand esports as an evolution of sports into the digitized society. For me, with a human resource background, this is nothing new and could be compared to the continuous transformation from blue-collar worker to white-collar worker, the move from body labor to managerial labor. Especially at the beginning of the computerization, many managers struggled with understanding the change in the work environment. Actual bodywork was replaced by mental work.

The following quote is from an operator in the seminal work of Shoshana Zuboff in 1988: “Managers come in here, and they think we’re not working if […] you are watching a screen. They can’t see you thinking. They can’t look inside your head. What is work now, anyway? It seems to me that our work has really changed, and our work is now a lot of sitting, and watching, and thinking” (1988: 293). Zuboff explains this that most operators were trained with this new technology, but the managers spent their time in the traditional work environment.

Nobody today would say that administrative work is not work, only because it is done with less body labor. Blue-collar work and white-collar work is just utterly different work and should be treated that way. That sounds remarkably similar to the discourse we currently observer in sports and esports. Esports no longer fits the categories the existing and traditional categories of sports, and maybe it is time to learn from human resource management. A blue-collar worker needs to be treated differently than a white-collar worker. That said, HRM is also struggling with the digitization, but, surprisingly, less than the sports world. Based on that, esports is something different; it is electronic sports, and, therefore, should be categorized differently.

What is esports, then? Above all, it is an allegory for the struggle of society to deal with digitization. Digitization changed the rules, and so did esports. It is a socio-technological phenomenon, and we observe in real-time a socio-technological concurrence (Scholz 2017). Technology enforces change in society, and at the same time, society enforces change in technology. If there is a misbalance, as observed in Germany, there is no advancement, and this society might stagnate. That should not imply that the role of esports has such a great impact on society, but you get a good sense of how society is dealing with the digitization.

Labeling esports as sports may seem insufficient and may not give credit to this digital phenomenon. The fourth industrial revolution changes the way sport can be understood. For the first time in sports history, the fundamental understanding of sports is challenged. However, esports will never replace sports, as blue-collar work still exist, but the relevance may shift. Still, in understanding the inner structure of esports could be helpful to deal with the struggle of transforming into a digitized society, then esports is about the person and the role everybody is playing.

Before deconstructing esports in delimitation to sports, two assumptions are made. First, esports is simply an umbrella term for over 400 titles than can be played competitively (Besombes 2019). That means the complexity of esports and the variety of esports titles may rival traditional sports. There is a fundamental difference between playing Counter-Strike and Hearthstone, as there is a fundamental difference between playing football and archery.

Furthermore, the sheer amount of potential games also puts the claim that game-developer abuse their power of owning an esports title into perspective. Players can choose to play the FIFA game or Pro Evolution Soccer; soccer players have to submit to the regulations of the FIFA. Second, esports is not only competitive gaming on a professional level but also an amateur level. This is an essential assumption for the discussion about the status of for-profit and non-profit in esports. Naturally, the professional level is for-profit, as this is the case in the majority of traditional sports. However, the amateur level is similar to many amateur teams in traditional sports. They meet up, play in a tournament or league, and have a good time. Both assumptions may be debatable, but they are necessary to compare esports with traditional sports accurately.

Looking back on the history of esports, it becomes evident that the connection to sports was not always the dominant driver for defining esports as it, esports was a sociocultural phenomenon. Michael Wagner stated that “eSports is a phenomenon that has become a fundamental element in today’s digital youth culture” (2006: 437) and in report of Superdata from 2015 it even summarized, “that a new phenomenon like eSports can be described in terms of the old is to misunderstand it entirely” (Superdata 2015: 3). Still, esports may not fit entirely into the sports category, but “it has its taste” (Arnaud 2010: 11). That the sports aspect is only one facet of esports, can also be seen in the seminal work of T.L. Taylor (2012), who focused on the interwovenness of esports in terms of play, work, and sport, as well as spectatorship. Therefore, it becomes evident that there is an ongoing discourse that esports may not fit in the category of sports.

As stated before, esports is linked with a cultural phenomenon and especially with a digital cultural phenomenon. Wagner said back in 2006 that it is youth culture, so it is assumable, that esports is no longer solely a youth phenomenon. Therefore, the esports culture had time to find its place in society and create structures, rituals, and tools to foster communities. The way communities are built varies vastly from the way traditional sports create communities. The physical aspect is not necessarily needed, and that makes esports a prime example for the way are built in the digitized world. Where is the benefit of playing at one location in a traditional sports club when people can play with people all around the world? Especially as in the digitized and globalized world, people always move. In esports, it is possible to play with an old school friend even though this person may live in a different country.

Furthermore, some people may prefer these digital communities over the physical club environment. They are not less social, but they have a different understanding of social. As these new communities, teams, clans, or guilds are in the digital/virtual world, they are not captured by traditional ways of measuring it. They are virtually invisible with the existing tools. Many people in esports do volunteer work in a variety of grassroots project and even the management of a team, the media coverage often neglects clan or guild. Esports is a digital phenomenon and, consequently, most of the community interaction happens on-line. The way communities are built different and, therefore, understanding esports may contribute to understanding digital communities.

Many esports players are nowadays also entertainer as well as the esports tournaments are designed to be entertaining. This development exploded only recently due to the popularity of Battle Royale games like Fortnite. These games and most importantly, the players are focusing on the entertainment aspect of their work (Friedman 2019). Examples like Tyler “Ninja” Blevins show the potential of an entertainer, despite not being the best Fortnite player, his exclusive partnership with the streaming platform Mixer immediately brought massive attention to this platform (Miceli 2019). But not only that, many players and esports organization test around new ways of entertaining their audience, be it through memes, drops or utilizing augmented reality in an opening ceremony like at the League of Legends 2018 World Finals having elements of augmented reality in it (Takahashi 2018). Esports is continuously pushing the limits of entertainment and, thereby, creating a novel category, the esports entertainer.

Finally, esports also had a substantial impact on the modern media landscape. Mainly due to the rise of live-streaming, esports, and video games, in general, contributed to a massive transformation in the media landscape. This development or evolution is, however, rooted in the negligence of traditional media towards esports in the mid-2000s. As no traditional media like television wanted to broadcast esports, besides South-Korea, it was necessary to find alternatives. Internet Protocol Television (IPTV) was the only way to stream tournaments, and with the emergence of Twitch.tv, this technology was broadly usable (Scholz 2019). Twitch filled a void and extended the watching experience with a social interaction dimension. Consequently, there was a motivation to watch the games online rather than go offline (Neus et al. 2018). People could watch from everywhere and be still able to interact. Furthermore, through Video on Demand, it was quickly possible to rewatch matches. Many traditional sports organizations try to experiment with ways to attract a young audience by enabling the use of a second screen mimicking the idea of social interaction through chat (Cunningham and Eastin 2017). It may be debatable, how strong the impact of esports was on the transformation of the media landscape through live-streaming, but esports was the driving force of live-streaming in the early times and had a significant role in the way the modern media landscape looks like. Esports pushed the limits of the media ecosystem and, most importantly, for this discussion due to the reason that traditional media ignored esports for too long. The actors in esports created their own media landscape and, by that, created a way to propagate content in the digitized society successfully.

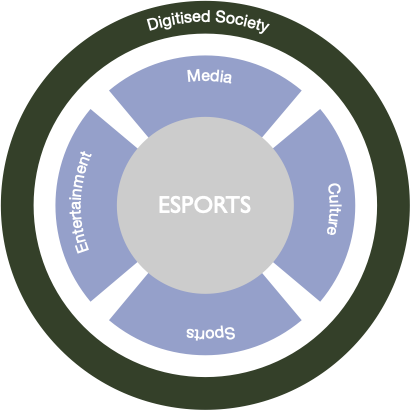

In summary, it becomes evident that putting a traditional label on esports is difficult, as it is something unique and requires different labels. Similar to the example of blue-collar and white-collar workers, it becomes evident that esports is an evolution of sports exposed to the digitization. As the digitization is a new transformative sociotechnical change for all of us, it also has an impact on media, entertainment, and culture. Deduced from this transformative change the following denotation of esports may be more fitting:

Esports is a cultural phenomenon with resemblance rooted in sports, media, entertainment, and culture, but emerged in a digitized environment. Thereby, evolved beyond the constraints of traditional sports, media, entertainment, and culture.

In the sense of Wittgenstein (1953), this should not be seen as a definition but rather an analysis of the usage of a word in society. This may not be useful as a legal definition but should describe the usage of the word esports in today’s world. As the current discussion show, esports is part of sports but not entirely part of traditional sports. However, it gave meaning to the word electronic sports. This logic can be applied to media, entertainment, and culture. Moreover, therefore, it seems that putting esports into traditional categories may not be productive at all, subsequently, using traditional regulation may also be harmful to the evolution of esports as the meaning of esports is forced into the sports category or any other category. That means esports is esports.

In the end, this proposed denotation is also revealing that an essential agenda for any person involved in esports should be, to fill esports with meaning. Esports is a case for a microcosmos of people based on the digitization. That means esports could act as a test laboratory for the digitized society.

How does this digitized society should look like? Therefore, discussions about esports being sports are only time-consuming, but instead, we should focus on the essential questions: How can we create a sustainable ecosystem for all stakeholders? How can we achieve the triple bottom line, which means a balance in social, environmental, and financial factors? What is an adequate form of regulation for a complex environment like esports? How can this complexity be managed without losing the flexibility and dynamic of esports? Solutions for those question will help to grow esports organically and sustainable. Furthermore, these solutions could initiate a discussion about the digitized society in which we want to live.

References

- Arnaud, Jean-Christophe. 2010. ESports – A New Word. In Julia Christophers and Tobias M. Scholz (Eds.), eSports Yearbook 2009 (pp.11–12). Norderstedt, Germany: Books on Demand.

- Besombes, Nicolas. 2019. Esports & Competitive Games by Genre. Accessed October

22nd 2019. - Cunningham, Nicole R., and Eastin, Matthew S. 2017. Second Screen and Sports: A Structural Investigation into Team Identification and Efficacy. Communication & Sport, 5(3), 288-310.

- Friedman, Daniel. 2019. Battle Royale Blurs the Line between Entertainment and Esports. Accessed

October 22nd,019. - Miceli, Max. 2019. Mixer Reaps Immediate Benefits from Exclusive Partnership with Ninja. Accessed October 22nd, 2019.

Neus , Florian,Nimmermann , Fred, Wagner, Katja, and Schramm-Klein, Hanna. 2019. Differences and Similarities in Motivation for Offline and online eSports Event Consumption. Proceedings of the 52nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 2458-2467.- Scholz, Tobias M. 2017. Data in Organizations and the Role of Human Resource Management. A Complex Systems Theory-Based Conceptualization, Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

- Scholz, Tobias M. 2019. eSports is Business. Management in the World of Competitive Gaming. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Superdata. 2015. eSports – The Market Brief 2015. NewYork: Superdata.

- Takahashi, Dean. 2018. Riot Games Uses AR Imagery to Kick Off League of Legends 2018 World Finals. Accessed October 22nd, 2019.

- Taylor, T.L. 2012. Raising the Stakes: E-Sports and the Professionalization of Computer Gaming. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Wagner, Michael G. 2006. On the Scientific Relevance of eSport. Proceedings of the 2006 International Conference on Internet Computing and Conference on Computer Game Development, 437-440.

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig. 1953. Philosophical Investigations. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Zuboff, Shoshana. 1988. In the Age of the Smart Machine. The Future of Work and Power. New York: Basic Books.