The Esports Integrity Commission (ESIC) hosted a one-day summit for key stakeholders in the esports industry to gather and share knowledge on the 13-14th April 2022. I had the pleasure of attending with help from the Esports Research Network (ERN), with many other members attending. It was a great opportunity to connect and see what the lessons learned over the COVID era and predictions on the future of the esports industry. There was a lot to digest, and so this article will present three key lessons resulting from the sessions and discussions at this event alongside my own perspectives.

Lesson 1: “Esports has always been, and will continue to be, reliant on the publishers and developers”

In the panel ‘Creating Effective Esports Policy’, Graham Ashton, the External Affairs Manager for Riot Games, outlined Riot’s approach towards governance for their esports titles. It was clear that they were very engaged with managing their esports scenes, both with third parties and internally. Whilst other stakeholders such as groups like ESIC and ERN are important to building robust governance structures, companies like Riot would have the most influence on how their title operates.

Developers & publishers will remain the key stakeholder and have the most influence on how their titles are governed. This does not prevent other groups from establishing structures for these titles.

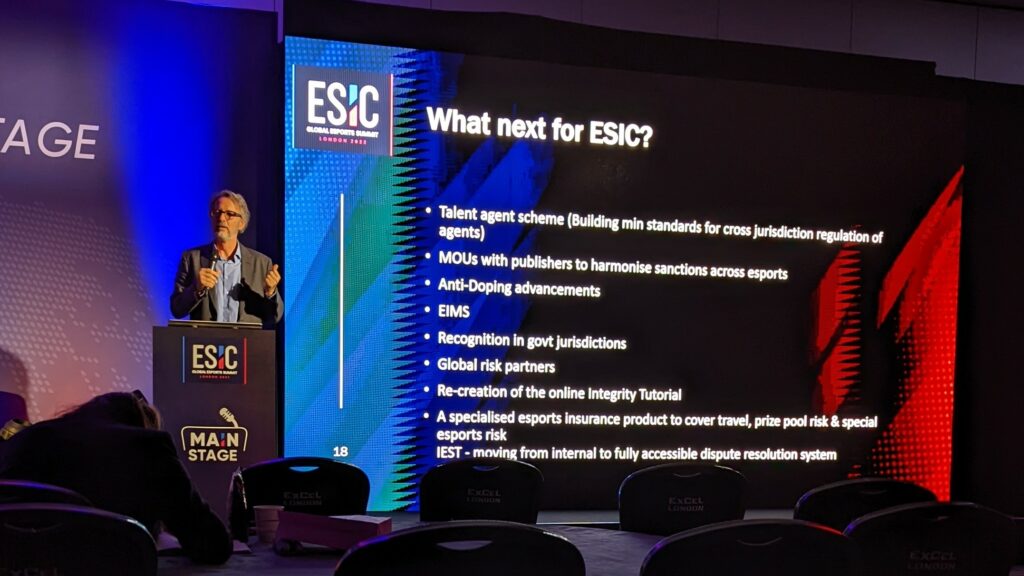

An example of how this could be an issue discussed by Ian Smith, Commissioner for ESIC, and Stephen Hanna, Director of Global Strategy & Partnerships at ESIC, in the panel ‘Bomb Has Been Planted – Crime and Punishment’. This panel discussed ESIC’s investigation on the exploitation of a bug in CS:GO by coaches. In short, the bug allowed coaches from a spectator view to see things that they wouldn’t see to gain an unfair advantage over the opponents. ESIC banned thirty-seven coaches from all member competitions, recommending non-member competitions to mirror said bans. In response, Valve gave out their own permanent bans to some of these coaches, some of which had ‘served their time’ on their ESIC ban. Both panellists objected to this approach during the event, claiming rarely were permanent bans ever justified, believing this case was not one of them.

These panels and the discussions had highlighted the unique governance that esports has. Because for-profit companies create the titles that esports competes within, the developers are usually the only stakeholder that can actually change how the game operates. This creates an entire governance structure dependent on the publisher/developer, so long as they choose to engage with it. It’s why the panellists for the ‘Creating Effective Esports Policy’ recommended against a single organisation responsible for the governance of many esports titles. They stressed that localised governance for each game is vital. An organisation could have gotten involved in Valorant, League of Legends, Rocket League, etc. but that each game’s governance must be independent.

Developers & publishers will remain the key stakeholder and have the most influence on how their titles are governed. This does not prevent other groups from establishing structures for these titles, but they must acknowledge that a developer/publisher’s own choices will usually supersede their own.

Lesson 2: “Esports commercialisation should be authentic and responsive to audience demand”

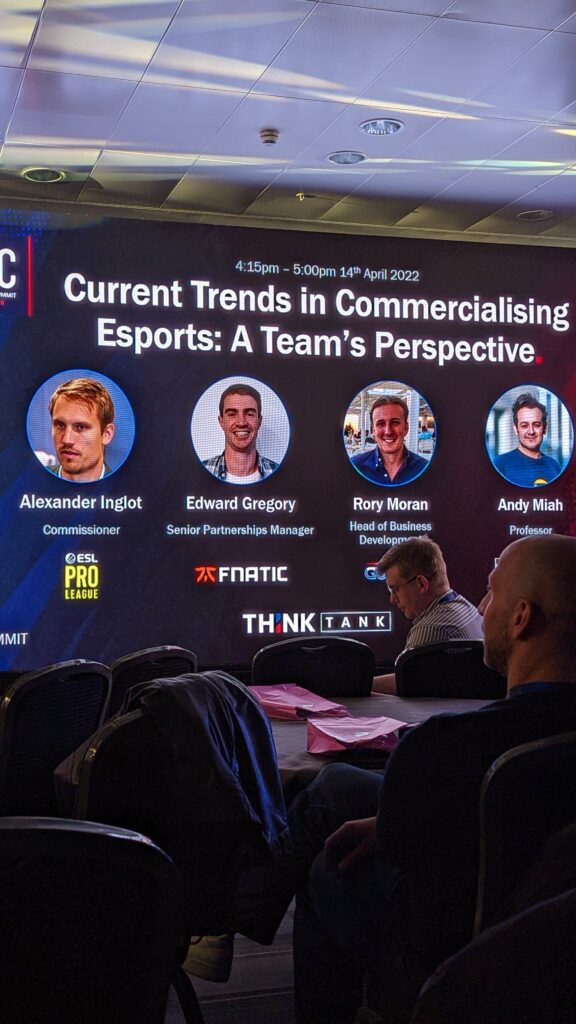

Edward Gregory, Senior Partnerships Manager for FNATIC, explored how their organisation adapted to esports transition from a niche towards a mainstream entity. Many of the partnerships FNATIC involved themselves focused on producing authentic products, such as BMW’s sponsorship of video content not driven by the nature of the sponsorship. Using the motto “United in Rivalry”, BMW sponsored five major LoL esports teams including FNATIC, encouraging social engagement through Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, and various streaming services. This encourages fans and teams to outdo each other through such mediums. Using competition to generate a natural desire to engage plants the idea that BMW treats esports seriously, not as an opportunity for a quick return.

Of course, companies seek to make a profit. Yet, a haphazard or inauthentic way of engaging with esports could ruin the image of the brand for a large number of people for quite some time. An example explored in the talk ‘PR and Communications in Esports’ by Kirsty Endfield from Swipe Right PR was Coca Cola’s ‘Real Magic’ ad. It showed an esports player competing in a fictional game, not an existing title, stopping mid-play to drink Coke. After that, the in-game avatar stops fighting and encourages everyone else to follow suit. To the intended audience this was a tone-deaf attempt at pandering, demonstrating a lack of understanding on how esports operates. The ad campaign is unlikely to have a notable impact on Coke’s bottom line, but for esports enthusiasts its reputation going forward will include that backlash, for both good and bad reasons.

Regardless of choice, it is important that results are authentic; naturally embedded within the esports ecosystem.

The main lessons from these talks was that for non-endemic companies engaging with esports, there seems to be two good approaches. The first is to partner with an endemic company, such as esports teams or tournament organisers on ad campaigns. Alternatively, they can have an esports branch of marketing & communications aware of contexts and attitudes of the target audience. Regardless of choice, it is important that results are authentic; naturally embedded within the esports ecosystem. A sponsored social media campaign promoting genuine rivalries between esports teams is well received; an advert featuring a fictional game and unrealistic behaviours around interconnectivity creates backlash. These outcomes are important to remember going forward.

Lesson 3: “Tournaments are the key to all esports”

Whilst obvious, competition is instrumental to the sustainability of esports. It’s easy to forget, amidst discussions on non-endemic engagement and governance, where the core of this industry is. The ecosystem depends on these competitions and tournaments, much like traditional sports. In a world returning to some level of normalcy from the pandemic, esports has had the luxury of growing during the past two years. Especially so when other industries and sports could not and esports was “the only show in town”. When the rest of the world were forced to learn online operation, esports had an easy transition in comparison. The industry had been adopting the blended experience for years, perhaps even decades. Despite this, there were still new challenges, especially around preserving integrity, highlighted by Ian Smith’s keynote talk ‘A year in review’. Ian presented examples of how there was a large increase in integrity violations & reports in 2020. He attributed this to more eyes being on esports as other sports shut down during this period.

The panel ‘Tournaments in a Post COVID-19 World’ explored other lessons learned during this period, with Michele Attisani of FACEIT, Andrew Haworth of BLAST Premier, and James Dean of ESL. What major esports organisers found was the importance of each company communicating with each other. Whilst rivals aiming to out-do one another, sharing lessons they learned was invaluable and something organisers claim to continue post-pandemic. When these organisers succeed, the industry succeeds. Teams have more leverage when approaching sponsors, more opportunities to innovate and develop, and esports continue to exist within the wider population’s consciousness and towards the mainstream.

When the rest of the world were forced to learn online operation, esports had an easy transition in comparison.

Beyond commercial considerations of events, Michał Blicharz’s talk on ESL Katowice touched on an important point on a tournament’s meaning. As Dominic Sacco of Esports News UK put it: “His talk cut through a lot of the noise of other keynotes in the space, to focus on the heart of esports: moments, memories and the human side of esports. He spoke about building a platform for players to create these big moments and show their emotional side”. Everything in esports is born from that ‘heart’, as it did decades ago. The key factor Blicharz claimed determined the success of an esports event was not metrics and fan satisfaction, despite their importance. Instead, it is making such events memorable and capturing the emotions that they create. Players are the core of the esports ecosystem, and so it is vital that we as an industry keep them at the heart of all that we do.

Summary

In short, the inaugural ESIC Global Esports Summit held up a mirror to the industry by those that engage with it. There was no need for an “Esports 101” session as pointed out by Stephen Hanna from ESIC. Everyone in the room engaged in the industry. It was an opportunity to dig deep into the successes and issues faced by the industry and will encounter going forward. There is a need for similar events, moving past the definitions of esports, whether it is a sport, and other surface-level discussions. When covering these basic concepts again and again, it takes time away from actually starting genuine change in the industry.

This summit is a sign of positive change in the industry.

Yet, an argument against this event was that it was particularly broad. From non-endemic investment and engagement, to tournament organisation and integrity, there was a cover in a single-day event. On the other hand, there has not been an event like this summit and so in time more specific events could emerge. Additionally, multi-day conferences could also be an option for more or longer debates. This summit is a sign of positive change in the industry; so now it’s time to see whether the discussions from this event result in action.